Seven Alternatives To The Dreaded Scrum Of Scrums

Scrum Master Peter Woolley writes:

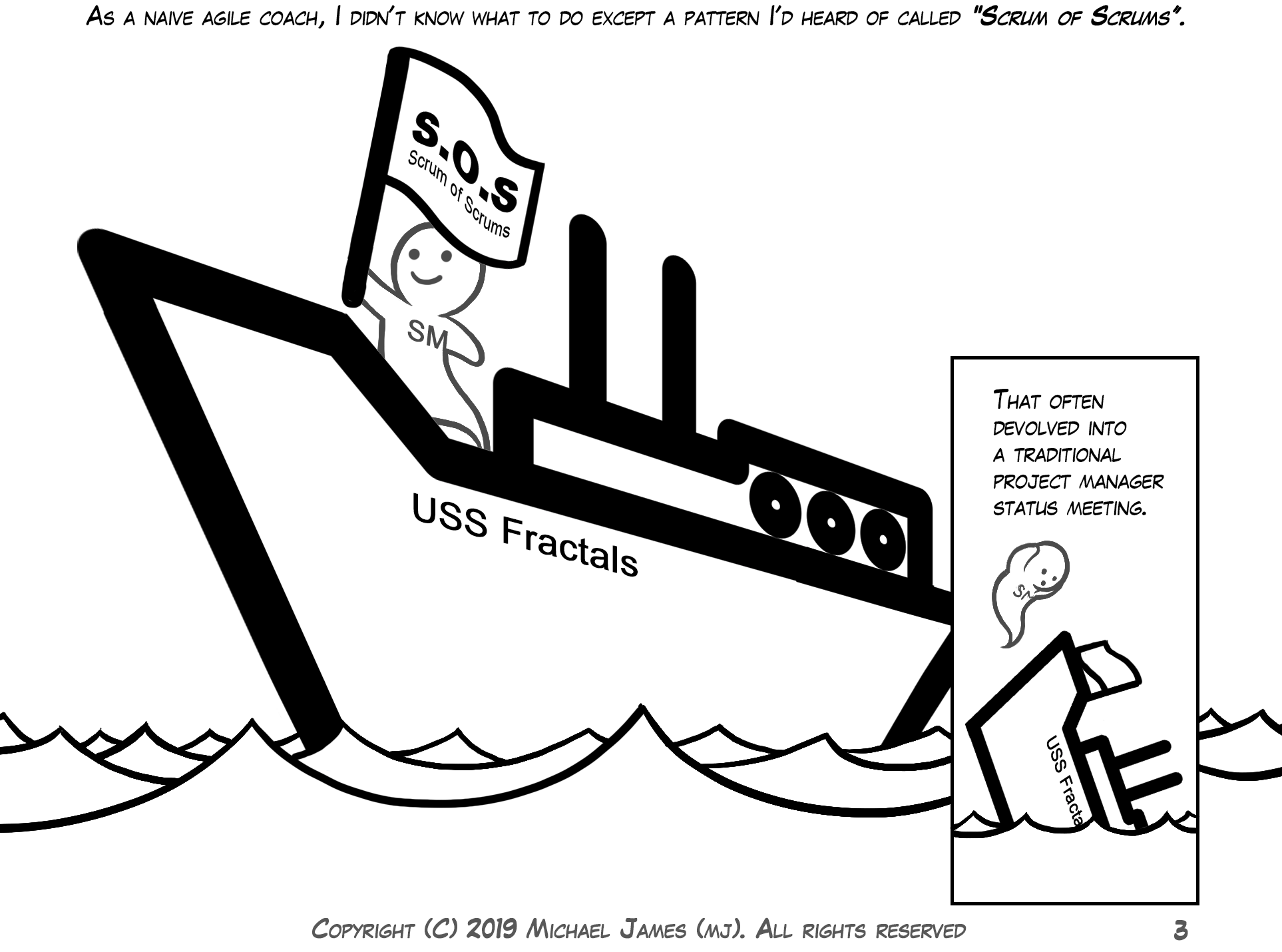

I have only seen Scrum of Scrums (SOS) work once, when SMs and POs met 3 times a week to share their premeditated conversations and working agreements at a feature level, frequently it descends into a round robin project update or a mind numbingly boring task level detailed update meeting where PMs confuse and confound each other.

I’ll start with the most practical link in this article. If you’re in a hurry, just go to the overview of the seven alternatives here: https://less.works/less/framework/coordination-and-integration.html

Back Story of Scrum of Scrums

The Black Book

Ken Schwaber and Mike Beedle published the first Scrum book in 2001. We called it “The Black Book” because of its obnoxious cover. They had a lot of abstract theory and just a bit of practical experience how to make Scrum work in a small context, but much less to say about multi-team endeavors. In what strikes me as almost an afterthought, The Black Book contained the idea of Scrum Masters from multiple teams meeting with each other regularly to coordinate. It had the catchy name “Scrum of Scrums,” reflecting the seductive fractal symmetry of the idea.

The Grey Book

Ken Schwaber wrote his best book ever in 2004: Agile Project Management With Scrum, a.k.a. “The Grey Book.” Please skip The Black Book, but you don’t really understand the modern Scrum Guide if you haven’t read The Grey Book. Unfortunately the grey book still included Scrum of Scrums, but fortunately had the improvement of sending team representatives (explicitly “engineers” in Ken’s 2007 book) instead of Scrum Masters. Ken’s last page (before the Appendices) contains this fascinating self critique:

When I [Schwaber] presented these case studies at a meeting of ScrumMasters in Milan in June 2003, Mel Pullen pointed out that he felt that the Scrum of Scrums practice was contrary to the Scrum practice of self-organization and self-management. Hierarchical structures are management impositions, Mel asserted, and are not optimally derived by those who are actually doing the work. Why not let each Team figure out which other Teams it has to cooperate and coordinate with and where the couplings are? Either the ScrumMaster can point out the dependency to the Team, or the Team can come across the dependency in the course of development. When a Team stumbles over the dependency, it can send people to serve as “chickens” [uncommitted participants] on the Daily Scrum of the other Team working on the dependency. If no such other Team exists, the Team with the unaddressed dependency can request that a high-priority Product Backlog item be created to address it. The ScrumMaster can then either let the initial Team tackle the dependency or form another Team to do so.

This was an interesting observation. Scrum relies on self-organization as well as simple, guiding rules. Which is more applicable to coordinate and scale projects? I’ve tried both and found that the proper solution depends on the complexity involved. When the complexity is so great that self-organization doesn’t occur quickly enough, simple rules help the organization reach a timely resolution. If self-organization occurs in a timely manner, I prefer to rely on it because management is unlikely to devise adaptations as frequently or well as the Team can. Sometimes the ScrumMaster can aid self-organization by devising a few simple rules, but it is easier for the ScrumMaster to overdo it than not do enough.

Ken’s CSM training materials and online discourse from this time on reflect his growing realization that the Scrum Master should have no authority over the team.

The Disavowal

At a Scrum Gathering (probably Stockholm in late 2007), Ken publicly disavowed Scrum of Scrums. Nearly every slide about it disappeared from his training deck. In a discussion group many years later, Mike Beedle expressed regret for the Black Book’s recommendation of using Scrum Masters as team representatives.

In 2008, Craig Larman and Bas Vodde wrote in Scaling Lean & Agile Development:

The most common misconception regarding the SoS is the assumption that it is the best or only way to hold a coordination meeting in Scrum. The SoS seemed a reasonable idea when first proposed (based on limited experiments), but there are alternatives that people now realize may work better…

SoS Meeting Recommendation Morphs Into A Structural Recommendation

Bas Vodde sent me this comment:

I think you probably want to distinguish two different Scrum of Scrums concepts:

1) The Scrum of Scrums meeting. Which seems to be in most of Ken’s writing and to be associated with SAFe. Most of the article is about that.

2) The “Scrum of Scrums” structural idea. This is what Cesario was referring about and is called “the Nexus” in Nexus. You ‘could’ think of an Requirement Area in LeSS of that (I do not, but can understand the argument).

My interpretation of history is that (1) morphed into (2) over time…

Bas

Why Scrum of Scrums Continues 16 Years After The Problems Are Known And 10 Years After Ken Disowned it

My theory is that Scrum of Scrums is like a bad song we can’t get out of our heads. I think other influential people (including Mike Cohn and Jeff Sutherland, who became a Scrum trainer in 2008) kept promoting it because we had so few agreed answers for organizations with more than 11 people. Scrum of Scrums is not in the Scrum Guide, but it is built in the two top-marketed “big box” approaches to scaling. Scrum of Scrums is semi-discouraged in LeSS (the less marketed approach to scaling) because we keep finding alternatives that are better at increasing an organization’s ability to learn and adapt.

Coordination & Integration: What To Do Instead

All excerpts from https://less.works/less/framework/coordination-and-integration.html

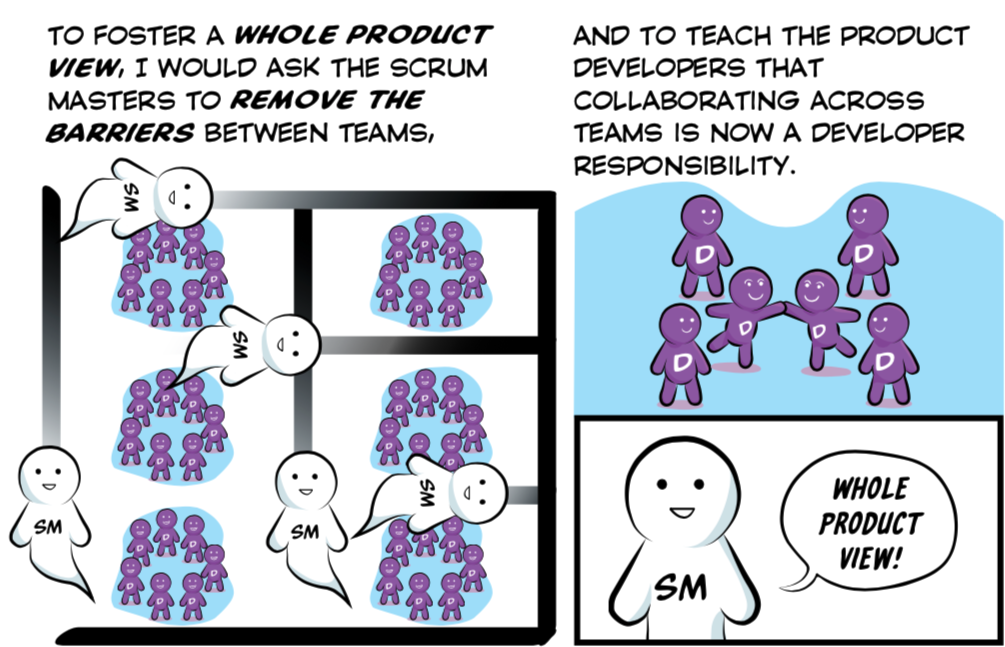

Scrum values decentralized, self-organized coordination and integration over the centralized, controlled coordination found in traditional project management. LeSS coordination and integration concentrates on how to support decentralized coordination while providing enough boundaries and structure to avoid chaos.

1. Just Talk

Probably the best way to coordinate between teams is to simply coordinate between the teams. Any member of a self-managing team would be able and expected to reach out to another team if there is an issue to be discussed. When there is a need for coordination then “just talk” by going to the other team, picking up the phone or, in the worst case, dropping them an email. You do not need a formal, official, usually slow coordination mechanism in order to coordinate. Get up and talk to people.

How do we know they’ll want to talk to us? In LeSS we try to remove the usual obstacles to that, such as teams are working for different Team Output Owners. Multiple teams work in one Sprint, toward one Sprint Review of one potentially shippable product increment. Scrum Masters should encourage inter-team collaboration instead of focusing on individual team output.

2. Communicate in Code

LeSS groups adopt continuous integration, which means that everyone has all their code checked in to the central repository mainline (branches are an unnecessary complication that should be avoided). Everyone in the product teams synchronizes with the repository several times a day and will get all the changes that other people have made.

So, when you update, spend two minutes going over the changes that were made by others and see if they relate to what you are working on now. If so, feel free to get up and “just talk” in order to synchronize your work with the others!

Branching is delayed integration! Merge problems increase exponentially over time.

What else makes Communicate in Code hard? The my code, your code practices and policies many companies have.

3. Scouts

A simple coordination method is for teams to explore their environment and send scouts to other teams or other interfaces. The scout monitors the interface and reports back to his team. Usually, teams do this during their Sprint Planning and select scouts for the length of one Sprint. The interfaces of the team could be another team, another product, something external to the team or a stakeholder… it doesn’t really matter what the team is scouting.

Unfortunately, some locally optimizing Scrum Masters try to prevent this! A Scrum Master with a Whole Product Focus would do everything possible to make this easy.

4. Component communities and mentors

People working on the same components at the same time need to know of each other so they can ask questions and review each other’s code. Do this by creating component Communities of Practice (CoPs), which should communicate via mailing lists, chat, occasional meetings, and other remote collaboration channels.

These communities are often organized by a “component mentor” who is usually a member of a feature team who has taken some additional responsibilities such as (1) being the teacher of how a component works, (2) monitoring the long-term health of a component, (3) organizing a component community, (4) organizing design workshops, and (5) reviewing code.

A component mentor doesn’t review code for approval before it’s committed. He’s a teacher and steward of the component, not a gate.

A component may have several mentors who share the work and thereby reduce key-person dependency.

Important!… Besides helping coordination, these practices help maintain or improve the code/design quality of a component, and increase learning.

One place I’m working with invited a component mentor from another team to help them with some code they weren’t familiar with yet, with the agreement that the mentor would not touch the keyboard! This might seem “inefficient” to someone who doesn’t yet realize the full cost of knowledge gaps.

5. Scrum of Scrums

A Scrum of Scrums meeting is a Daily-Scrum-like meeting between teams, typically held two or three times per week.

Usually the format is three questions, similar to a Daily Scrum:

- What did my team do that is relevant to other teams?

- What will my team do that is relevant?

- What are my team’s obstacles that other teams should know about or can help with?

Naturally, use and evolve whatever questions your group finds useful.

A caution: The desire to hold a Scrum of Scrums can be a sign of unnecessary dependency or coordination problems caused by single-function groups and component teams, or by teams not able or willing to identify and do shared work.

Scrum of Scrums isn’t a part of LeSS and as a more formal centralized coordination technique, it is also not recommended. That said, if it is working, please don’t stop doing it… yet don’t feel you must do it because of adopting LeSS.

If you decide to do Scrum of Scrums meetings anyway, remember to rotate team members. And of course you wouldn’t send Scrum Masters, since they have no authority to coordinate teams.

6. Multi-team meetings

It is common for some teams to need to work closely together whereas others may not feel that need. For teams that work closely together, it is common to have multi-team LeSS meetings. Some examples would be:

- Multi-team Product Backlog Refinement

- Multi-team Sprint Planning Two

- Multi-team Design Workshops

- Exchange members in Daily Scrum.

Are you seeing the theme here? Only have the meetings you need. If you’ve been to an Open Space Conference, you know The Law Of Two Feet requires you to use your two feet whenever you’re not learning or contributing.

7. Travelers to exploit and break bottlenecks and create skill

Sometimes a product group relies on a couple of experienced technical experts. How can the knowledge of these (scarce) experts be kept available to all teams? They can become travelers. Each Sprint they join a different team, coaching via pairing, workshops, and teaching sessions.

Although travelers are not specifically created for coordination, by joining different teams they create or strengthen a broad network, which is exactly what is needed for informal coordination channels. And they increase the consistency of some knowledge or practice across teams, realizing a coordination goal.

Once when I helped teams reorganize (using a team-self design workshop) I was surprised that several specialists did not want to join teams and opted to call themselves travelers instead. But a few months later, they had settled into teams.

8. Leading Team

In some domains, features are monstrously large. When you split these giants into smaller Product Backlog Items, it can require many teams working closely together, each separately on its own PBI, to create a single monster feature.

Another technique for coordinating teams working together on the split items of a big related feature is a leading team. A leading team is just a regular feature team that takes a leading role for the overall giant feature. In addition to doing development work, they are responsible for keeping track of what the other teams are doing and helping them synchronize. In short, they organize cross-team coordination related to the giant in addition to themselves doing development.

Sometimes several teams start implementing the giant at the same time. At other times, the leading team starts alone to focus the early knowledge transfer and simplify the creation of a cohesive design. After a few Sprints, more teams join. In this case the lead team also has a teaching responsibility to help the incoming teams learn what they already know.

Do not underestimate the power of a single team in an optimized environment! The development director of one place I worked with in local government told me that as he introduced Scrum he realized he really only had one capable team out of his 40 employees. In another famous story, over 100 contractors for the FBI were unable to get anything done. The solution was to use a much smaller group in the basement of the FBI Headquarters.

Japanese version: 面倒なスクラム・オブ・スクラムに取って替わる7つの方法